Should I give equity to early employees? Yes, here’s why

Last updated: 19 April 2024

Manage your equity and shareholders

Share schemes & options

Equity management

Migrate to Vestd

Company valuations

Fundraising

Launch funds, evalute deals & invest

Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV)

Manage your portfolio

Model future scenarios

Powerful tools and five-star support

Employee share schemes

Predictable pricing and no hidden charges

For startups

For scaleups & SMEs

For larger companies

Ideas, insight and tools to help you grow

12 min read

Ifty Nasir

:

Updated on September 3, 2025

Ifty Nasir

:

Updated on September 3, 2025

Last updated: 14 August 2025

Once you’ve made up your mind to create a company share scheme, the first questions that spring to mind may look something like this:

These are common questions, and your research so far may have led you to believe there are no easy answers.

However, we’ve learned a few simple tips and formulas that make it easy to calculate the appropriate amount of equity to set aside for your growing company and its employees.

In this post, we will take you through step-by-step. First starting with the amount of equity you should reserve for your team.

First, before assigning any equity to individual employees, you’ll need to decide how much you’re going to allocate for the option pool used in your share scheme.

Overall, the total amount of equity you set aside will typically be around 5–20%.

This value is based on what we have seen Vestd customers assign to their share scheme. Your equity amount will depend on a few things including:

If you founded the company alone, setting aside 20% equity for employees leaves you with 80% for yourself. However, if there is a founding team involved, you’ll want to consider how the employee equity will dilute each of your shares.

Consider your cap table.

If you’ve taken on external investors, you’ve already issued equity. Issuing too much employee equity could dilute both your shares and the investors’ significantly, and any future shares would continue to dilute what anyone else (including employees) have already received.

If you are setting up an EMI (Enterprise Management Incentive) scheme, you will submit your valuation to HMRC (Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs) for approval. This also sets the total value of shares able to be issued to recipients.

Let’s look at a few examples that will help you make a smart decision about how much total equity to set aside for your employees.

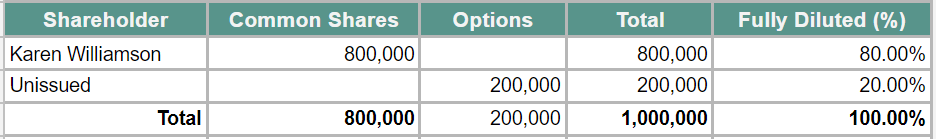

This is perhaps the most simple cap table you will find. It shows what you would see for a bootstrapped company with a single owner who holds nearly all of the shares themselves:

Even if our example founder hadn’t reserved any equity from their initial 100% ownership, doing so now would bring them exactly to what we see here: 800,000 shares for them and the rest unissued.

From these unissued options, they can award a per cent (or two) to high performers, critical hires, and so on.

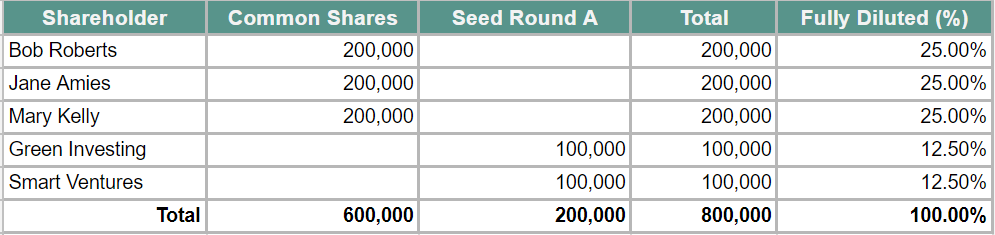

Let’s have a look at another example of a somewhat more mature company, with multiple founders and some investors already on board.

In this particular example, we have three members of the company’s founding team, as well as a seed round that brought on two investors, each with a 12.5% stake in the company:

However, this particular company hasn’t yet issued any options for an employee share scheme.

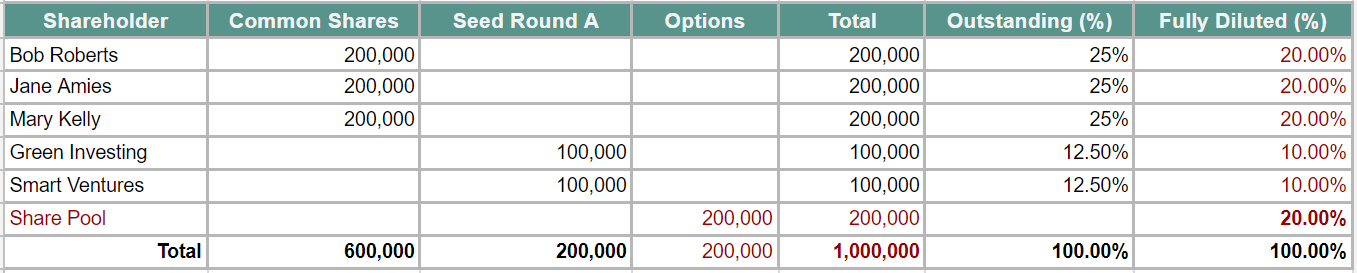

Once the share scheme is established, the cap table (including future option liabilities) may look something more like this. (New additions and changes have been noted in red).

As you can see, the addition of a 20% employee share pool will eventually reduce each shareholder’s investment to 20% (each founder falls from 25% to 20%, while the investors drop from 12.5% to 10%).

However, because the value of each share should increase over time, this only reduces the percentage holding on the company, not the potential profits gained from holding the shares or exercising options.

For a more in-depth look at dilution, and how the addition of a share scheme might impact fully developed companies with investors and additional fundraising rounds, we recommend reading our Equity Fundamentals guide.

Once you’ve taken these factors into consideration and settled on an appropriate amount of equity to reserve for your employee share scheme, you can proceed to the next steps: learning how to assign equity to individual employees and deciding how much is appropriate for each one.

There are often two early phases in the life of a company:

The initial phase, in which many employees who join are often acting almost as a co-founder due to the amount of work they tend to assume without meaningful compensation in return

The growth phase, in which your company is becoming more stable, scaling its efforts, and hiring employees who typically do not feel as if they are taking a risk by joining

It’s most sensible to award equity to members of your team based on which phase they joined you in.

The foundational employees who joined you in the earliest days deserve compensation for the share of the work they assumed, and the amount of financial risk they may have taken.

You still want to give later employees a feeling of ownership in your company, of course, but you must be very mindful of both dilution and the feelings of your early employees when you do so.

Let’s review this idea in-depth, beginning with the amount of equity you should give to the earliest employees.

For critical early hires, you should offer percentage points (in the equivalent number of shares) of your equity pool as part of their total compensation package.

This percentage can be as much as you feel comfortable with but should be dependent on the employee’s contribution to your company. For example, a director could earn 2–3% of the available pool while a senior contributor might receive 1% or less.

If you aren’t certain which of your employees qualifies as “foundational,” it may help to know what other UK companies are doing. Reports over the years have shown that the roles most often rewarded with percentages of equity are:

The time at which these hires join may also affect the amount of equity you decide to offer. Venture capitalist Leo Polovets analysed Angel List job postings to find the average percentage points extended to the first few hires:

](https://www.vestd.com/hubfs/Imported_Blog_Media/1_bCK-RfX0lBOpnzToZjEDTw.png) Graph from Coding VC

Graph from Coding VC

](https://www.vestd.com/hubfs/Imported_Blog_Media/1_ns49xH_XGhD95Zu_nkEgoA.png) Graph from Coding VC

Graph from Coding VC

Who you reward with significant equity depends on when they joined, and how your company functions (or may function in the future).

For SaaS companies, for example, it may make more sense to reward equity to designers and marketers than it might if you were operating a physical store.

Also, remember: if your company is still young, you may want to reserve equity for future crucial hires (like a CMO or experienced engineer). They will likely expect options upfront as part of their total compensation package.

The equity you provide to early employees is designed to reward them for their hard work and ongoing loyalty and to create a foundation for your share scheme.

Once you’ve established this foundation, and your company has begun moving toward a growth phase, you need to create a plan for providing equity to your other hires (both current and future).

When providing shares to your other employees, the key is to create a plan that will allow you to do so systematically.

Rather than giving percentage points of equity to individuals based on how you value them, you will give equity on the basis of where each person fits into your company structure.

The best way to create this plan is to first organise your company’s team members into groups. Then, after the groups are created, you will assign a set value of equity to each one.

Finally, as new members join or existing members are promoted, their equity will be determined by the group they are assigned to.

This model for sharing equity with employees on the basis of their roles, rather than in the form of individual percentage point grants, is known as the employee share ownership plan (or ESOP) model.

With this model, you are essentially creating a “pool” from which all current and future shares are taken.

It includes the percentage point grants you’ll give to early or valuable employees, and the pre-determined amounts of shares you’ll give to others. It also leaves room for later hires who may necessitate percentage points.

](https://www.vestd.com/hubfs/Imported_Blog_Media/1_WG_1Zdf_KoGu3z1RNyyqJQ.png) Illustration by Balderton Capital

Illustration by Balderton Capital

Let’s look at one example of how a company might create employee groups with pre-determined equity assigned.

In this case, on the basis of both the employees’ roles and their seniority within the organisation. (In the chart below, FDE stands for “fully diluted equity”).

](https://www.vestd.com/hubfs/Imported_Blog_Media/1_k1wQqzaSbOPzRGbyqT8I2g.png) Graph from Index Ventures

Graph from Index Ventures

In this example, the groups are based on four tiers of function within the company (the highest being engineering, the lowest being marketing), then broken down further by seniority.

When a new junior engineer is hired, they receive a standard amount of equity. And when that engineer moves from junior to mid-level to senior, their equity is adjusted to match exactly what others have received.

The decisions you make with regards to your groups, seniority levels and the amount of equity assigned should be based on what your company does and how much revenue each section or role generates.

For example, if a single client might be worth £500,000 per year in revenue, it would be more sensible to reward each sales hire (the people directly responsible for bringing in these clients) with a larger equity share.

Ultimately, in order to avoid allocating too much of your company’s equity (and dramatically diluting the stakes you, other founders, or investors have in your success) you must move to an ESOP model as soon as you feel it is appropriate.

Vestd customer data 2023

At this point, you should be certain of a few things:

Now you must determine exactly how many shares to award those non-foundational employees.

Although this step sounds complicated, it does not have to be a time-consuming effort. It will require some initial work on your part, but once you decide on a formula to use, it will become a repeatable process.

Let’s look at two ways you can build a formula to determine how many shares to award your employees, and how to use each one as part of your employee share scheme.

This first formula, made popular by venture capitalist Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures, calculates exactly how many shares to give each of your employees on the basis of:

Wilson’s formula is based on the monetary amount of your equity, as he explains here:

"I got this formula from a big compensation consulting firm. […] It is based on a common practice in compensation consulting. And it is based on the dollar value of equity."

With this formula, you will be able to explain to a team member the value of the equity they hold.

For example, if they have been given 40,000 shares at a value of £3.25 per share, it’s easy for the employee to do the math and determine what their shares are currently worth (£130,000).

They can also see how this value might grow as the company’s valuation changes over time.

Here is how to use this formula to assign shares per employee, step-by-step:

Establish your valuation

If you have an EMI scheme, you should use the valuation you have established with HMRC.

Establish the number of shares

The total number of shares in your company share scheme, including those you’ve already issued.

Create “brackets” of employees

Wilson suggests four brackets, but you can create more or less depending on the structure and/or salary ranges of your organisation. The brackets might look like this:

If you followed the steps earlier in this post (with regards to organising your company into sections), you may already have these brackets in place, but you may want to redefine them based on salary or other factors.

Assign a multiplier to each bracket

You would then have something like this:

Run the multiplier against the employee’s salary to come up with a monetary value of equity

You can use what seems best in this situation; if you are paying below market value, you can use a higher amount to give the employee the right to more shares.

Divide your company valuation (step 1) by the number of shares (step 2)

This will give you a current price per share. You may already have this information if you are offering an EMI scheme.

Divide the monetary value of equity (step 6) by the price per share (step 7)

You will finally have the number of shares that your employee will have the right to purchase, as well as a current approximate value per share.Let’s walk through an example of this formula in action so you can better understand how to use it.

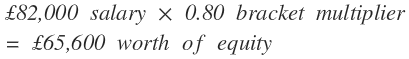

Your company, InVestd, has hired a Director of Sales. Their current salary is £82,000 per year. Let’s determine how many shares to offer following the steps above:

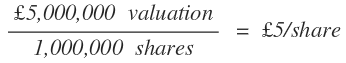

Let’s say you are preparing to hold a round of fundraising. Your current valuation is £5M. We’ll also say you currently have 1M total shares in your company share scheme.

This new hire falls under the top bracket you’ve set for director-level employees, and you’ve decided to apply a salary multiplier of 0.80x to this bracket.

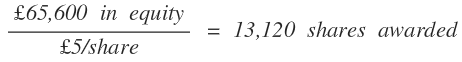

First, multiply the director’s salary, £82,000, by their bracket multiplier to receive the monetary value of their equity.

Next, divide your company valuation by the total number of shares in your share scheme to receive the current market value of each individual share. You will need this in the next step.

Finally, divide the equity value above by the value of each share = 13,120 shares. This is the number of shares you will award your new hire.

You can express this to the director as “you have been given the right to purchase 13,120 shares, with a current market value of £5 per share.”

There is no initial tax liability for the director on the shares, but at the time of exercise, they will be subject to income tax on any difference between the market value when granted and the exercise price (plus Capital Gains Tax on exit, possibly at a reduced rate).

One thing your employees should remember is that the current value of these shares may seem nominal, but as your business grows, it will increase. The current value of each share is not nearly as important as the future value, and how it will change over time.

But this information should still be shared to give each employee an idea of what their ownership stake looks like, and so they are aware of any future tax implications when they choose to exercise their options.

Wealthfront, a financial planning company, has publicly shared its own four-part plan for awarding equity to new hires, promoted employees, outstanding performers, and employees who have been with the company for a set period of time (so-called evergreen grants).

The most relevant aspect of the plan at this moment is the method they use to award equity to new employees. By doing calculations with the market rate for these individuals rather than salary.

To put it simply, if an employee is hired at £100,000 per year, but the salary for this role in a major city is £150,000 per year, Wealthfront will award the employee the difference between the two in the form of equity. In this case, £50,000 in shares.

It may also be useful to go above the market rate in some instances. Say an early employee is not quite convinced that they should take the risk to join your company, or an unstable market could cause the value of your shares to climb slowly.

You can opt for a standard addition of, say, 20% above the market rate. So using the example above, the employee would be eligible for £80,000 in shares instead.

This method is especially useful since nearly all companies in the startup phase cannot afford to pay their talent the very best salaries or compete with large tech companies.

But you can still reward them with a total compensation package in line with what they would expect elsewhere, and a meaningful investment in your company that should continue to grow in value over time.

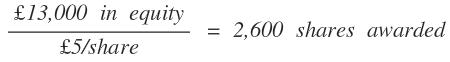

Let’s look at an example of how you might use this method.

Again, we’ll say your company has hired a Director of Sales at a salary of £82,000 per year. Let’s determine how many shares to offer following the steps above:

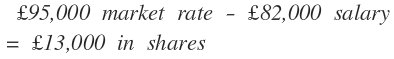

Using data from websites like Glassdoor, PayScale or Indeed, find the market rates for this employee’s role. We can see that some larger UK-based tech companies pay their sales roles upwards of £95,000, so we’ll use that value.

This means you will award the employee the right to purchase options, currently worth approximately £13,000:

To determine the actual number of shares to reward, you will need to have your company valuation and the number of shares in your company share scheme available (as with the Wilson method above).

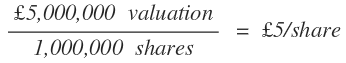

Divide your valuation (we’ll stay with £5M) by the total number of shares, 1M, to receive your current market value per share.

Finally, divide the monetary value of shares by the value per share. This is the number of shares you will award your new hire.

As with the Wilson method, you would express this by saying “I am giving you the right to purchase 2,600 shares, with a current market value of £5 per share.”

Or you could simply say that you have given them the right to purchase £13,000 in shares to make up the gap between their salary and the market value of their role.

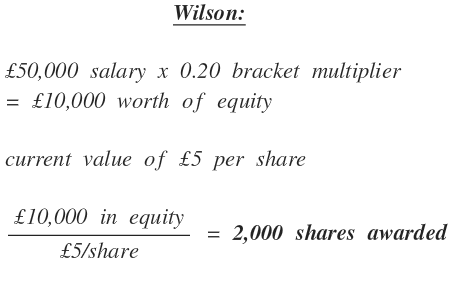

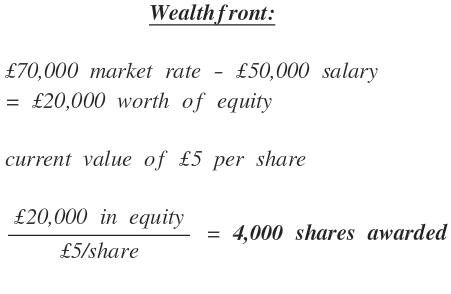

Let’s do a side-by-side comparison of these two options for calculating the number of shares to award an employee.

In this example, your company has just hired a marketing manager at a yearly salary of £50,000.

Your current valuation is £5M, and you currently have 1M total shares in your company share scheme (so we will keep the previously stated £5/share value).

For the purpose of the Wilson method, this new hire falls under the third bracket you’ve set for employees who are managers or other critical hires but not yet in a director or executive role. You’ve decided to apply a salary multiplier of 0.20x to this bracket.

For the purpose of the Wealthfront method, you have done research to determine that the market rate for this role and level of experience at public UK technology companies is £70,000.

Let’s now perform the calculations side-by-side to see how many shares this employee would be eligible for in either scenario:

As you can see, the Wealthfront method gives this employee the right to double the shares vs. the Wilson method.

If you are unsure which method to opt for, you may want to apply both formulas and consider the results.

The salaries, market rates, and current share values used may have a drastic impact on the number of shares awarded, and you might find that one method awards more equity than you are comfortable giving away to any one person.

Either one of these formulas will give you a consistent, repeatable method to help you reward non-foundational employees with appropriate amounts of shares, based on their role and contribution to your company.

Work out how many shares to give to your team using our handy calculator.

Now that you’re armed with the knowledge of how much equity to set aside for your employees, you are now nearly ready to start your company’s share scheme.

If you’re like a lot of other business owners who have been putting off this process because the facts and figures are confusing, we hope this breakdown has been useful to you.

And we hope you’ll join the thousands of UK business owners who use shares to incentivise their teams. Book a free consultation with one of our equity experts today and get started.

Our team, content and app can help you make informed decisions. However, any guidance and support should not be considered as 'legal or financial advice'.

Last updated: 19 April 2024

Last updated: 1 October 2024. The founders we talk to want to share equity with some or all of their team. They agree that it’s the right way to go,...

Last updated: 18 April 2024